“The universe has no center and no edges; reality is arbitrary.”

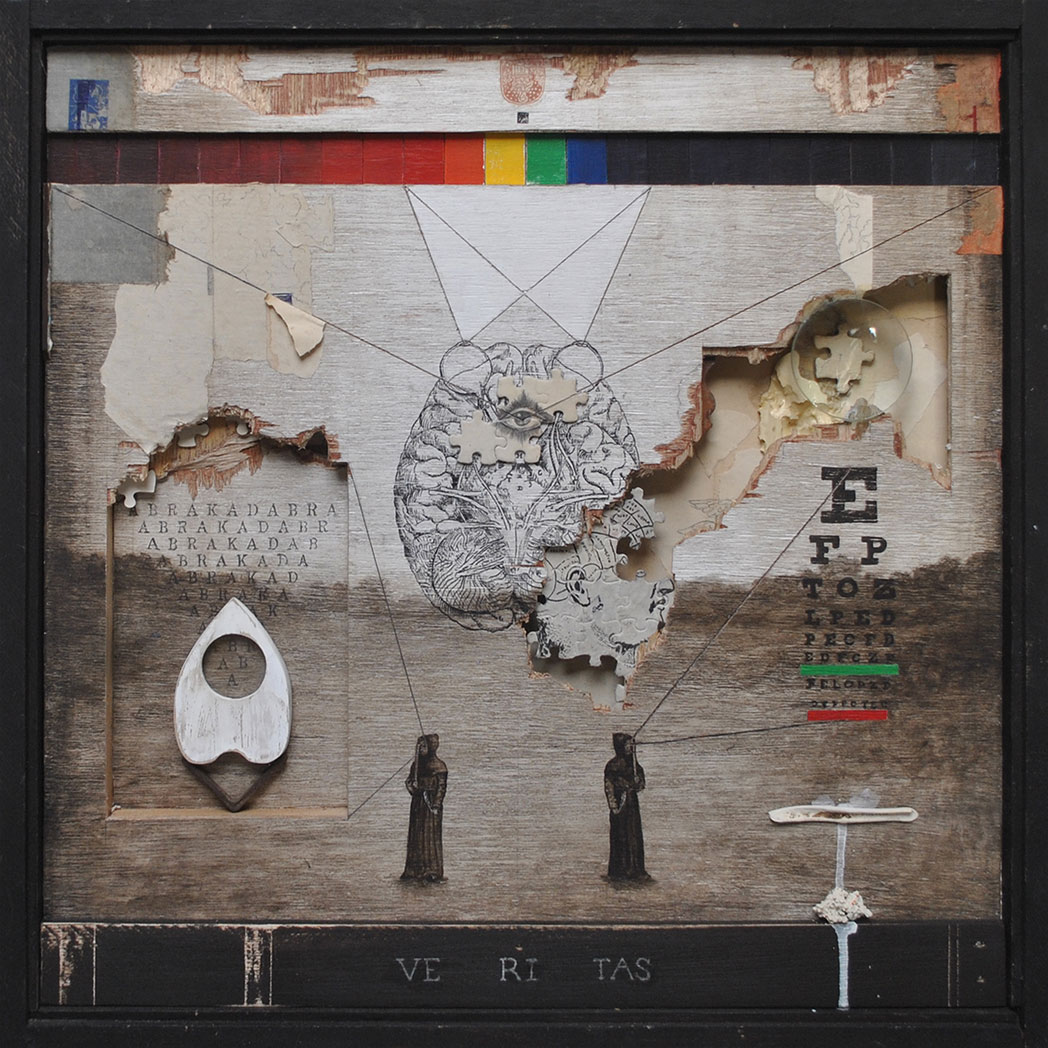

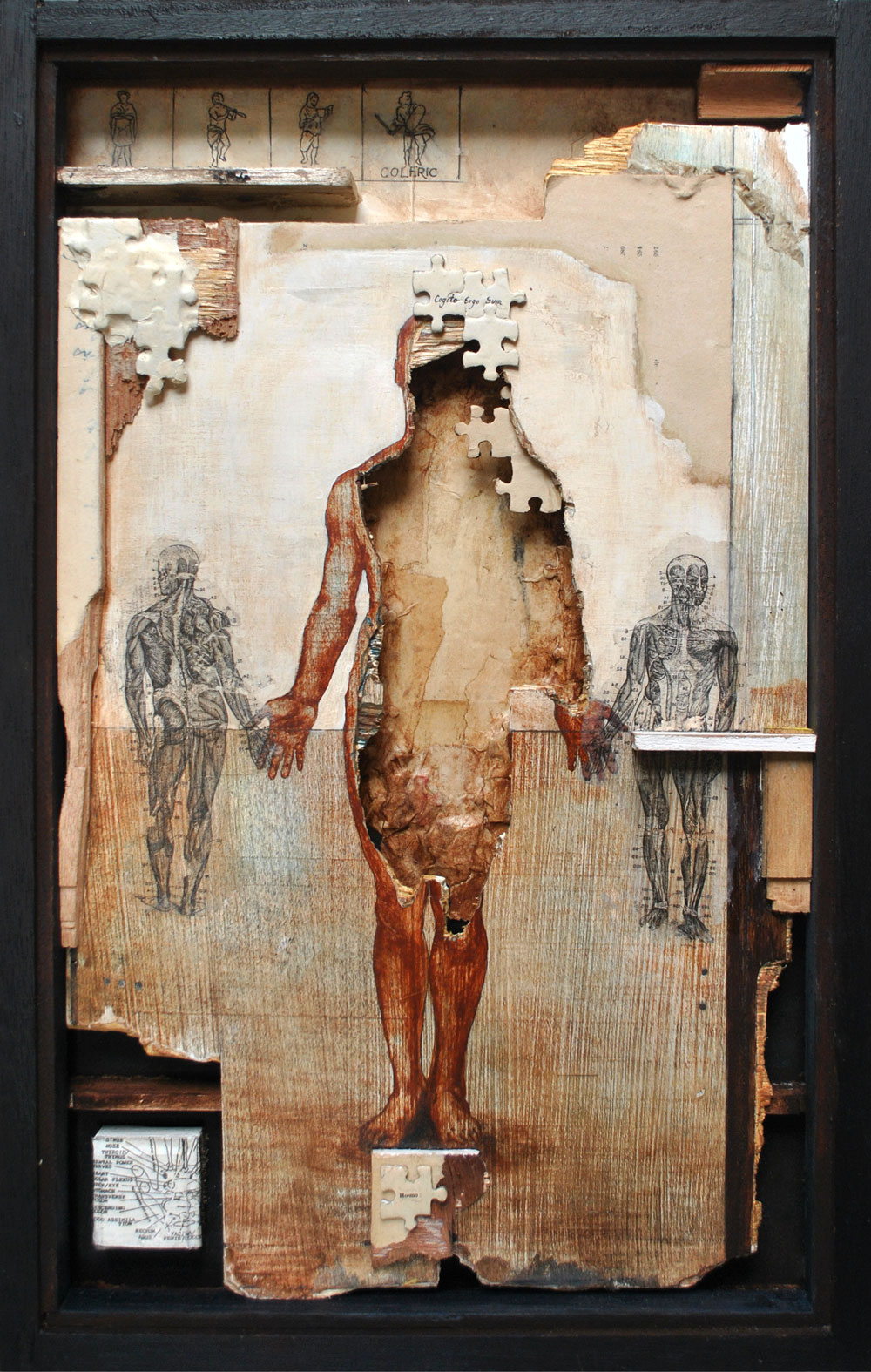

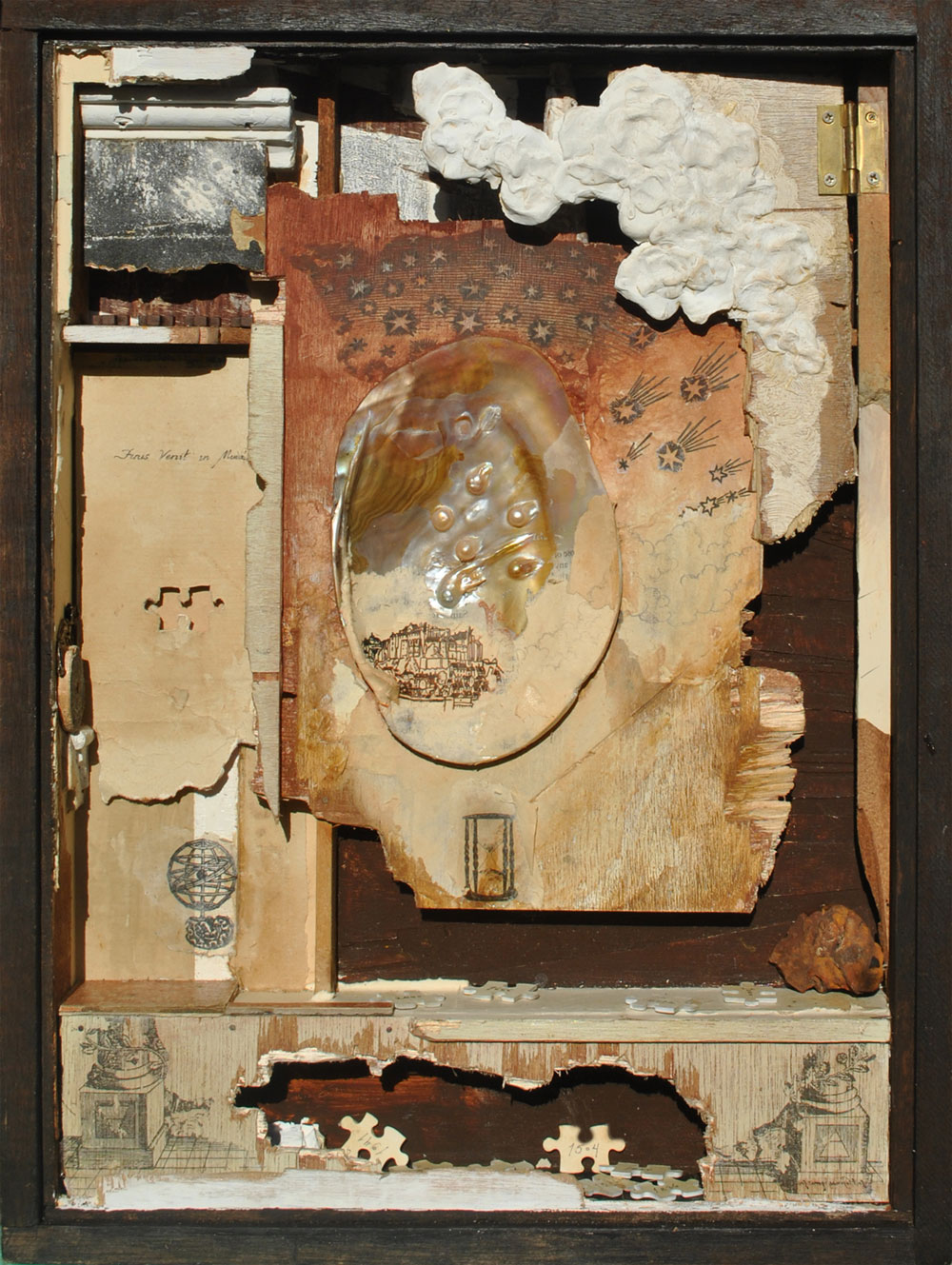

In Ioannis Sicuya’s works, we see anatomical diagrams, illustrations of the human brain, depictions of heavenly bodies, images of various cryptids, and other esoteric imagery, but common to all works are the use of jigsaw puzzle pieces alongside crudely broken pieces of plywood and crumbling patches of paper. The marriage of symbolisms and materials serves the artist in probing into the cracks inherent in human perception ergo experience, and the consequences springing from these fissures.

The artist, in his first solo exhibition, emphasizes the limits of perception. Aside from the fact that our psyches are shaped by our material conditions—concepts emanate from what we frequently encounter—we, biologically speaking, lack the capacity to cover the full range of stimuli prevalent in nature: for one, the photosensors in our eyes can only recognize frequencies from a fraction of the electromagnetic spectrum. However, our brains have adapted over time: Gestalt psychology suggests that we tend to fill in these gaps, arguing that our brains are wired to privilege wholes and totalities over parts. This enables the distilling of meaningful information from noise and chaos, a tendency that the term “apophenia” specifically refers to: we are said to spontaneously perceive patterns given a flux of random data, manifestations of which are noticeable in both gambling and fortune telling, and in phenomena such as mentally correcting typographical errors and seeing faces in inanimate objects or the figure of Jesus Christ on a piece of toast.

The introductory quote, taken from the 2009 film The Limits of Control where it was intermittently recited throughout almost like some hypnotic mantra, suggests that reality is formed in our minds, built out of information attained from accumulated experiences in conjunction with the theoretical, tailored to describe the sphere of existence we inhabit. Notions of “center” and “edge” are revealed not to be innate properties as we often take for granted rather they are concepts we ascribe to objects we are capable of observing, entities that are independent of the human mind. However, numerous reports of phenomena observed—seemingly strange in nature, exhibiting mysterious behavior—whose existence, from our point-of-view, comes across as questionable. The artist is inclined to believe that when such bizarre and foreign happenings occurred, our ancestors circumvent its autonomy by altering their beliefs accordingly in order to assimilate them. And so, myths are born.

A certain tension suffuses Assuming It’s Apophenia, one between the notion of myths as narratives constructed to compensate for our perceptual constraints—thus an inability to deeply comprehend the world—and the idea that these are “myths” relative to our frame of knowledge. To some, these are world views that govern daily life, not consciously constructed rather naturally blossoms to assist one in grasping the complexity of the universe. The former suggests itself as absolute and essentialist, grounded on scientific knowledge; the latter, more speculative. Although, one must remain cautious not to substitute the former, a view desiring the obsolescence of myths, over the latter for doing such imposes a Western paradigm of rationality and skepticism over other forms of knowledge. The belief in “myths” might be hindering us from truly understanding the world just as “rationality” might be blinding us from seeing the bigger picture—to insist the superiority of one might mistake the silhouette for the actual object, the trunk for the entire elephant.

Sicuya mostly explores these hazy fields and points of contention: the limits of perception and the adaptation of thought, the birth of myths, and the fragility of concepts valued by society yet too often taken-for-granted. As such, dictionary texts, jigsaw pieces, optical charts, Ouija, astronomical, and cryptozoological imagery are deployed in myriad juxtapositions and configurations in an attempt to blur the boundaries between the empirical and the pseudoscientific, exposing all as unstable as we typically overlook. Each work serves as leveled terrains, smooth spaces where both fields operate synergistically. Words like “nationalism”, “authority”, and “sacred” appear in some works with the intention of categorizing them not as “myths” per se but to be debunked as heuristic concepts—not ideas conveying eternal essences but devices resting on wobbly prosthetics that nonetheless possess, although perhaps temporary, invaluable utility. The broken plywood and crumbled discolored paper occupied by the other materials are strategically utilized by the artist to emphasize the idea of not only construction but also nature, pointing to their origins and their subjection to decay; as if declaring everything as concepts, whether synthetic or organic, as illusions worth shattering or at least deconstructing in order to further understand the plethora of signs, ideas, and entities that pervade the universe—regardless of the possibility of ever grasping the sheer totality of it all.