The artist Leo Abaya is keenly aware of the staggering statistics that pervade the current social and political climate. These data and metadata have a certain density to them, not to mention ubiquity to the degree that they are invoked briskly to dramatize reality, craft policy, sketch out situations, speculate on scenarios, and so on. Data, however, are discourses, too. They come to being through the techniques of making them: there is method that renders them actually opaque, although at first blush they seem transparent and natural. In fact, that they appear to be so is an achievement of the interests that efficiently and decisively turn them into seductive instruments. Or it could be that they are instruments from the very start.

Abaya in this exhibition tries to pierce through the abstractions that these data have become. In his own words, “I resent the lack of compassion in fiscal policies that are based on quantitative statistical data on people. This resentment comes from the fact that numbers, by themselves, can deceive or obfuscate actual human condition; that the innate structuralist nature of quantitative data pertaining to people subordinates functionality.” Thus, instead of merely reciting them and deriving from them circumstances and consequences that have everything to do with life and death, bread and butter, he creates conditions for them to be sensuously engaged. Such a bodily engagement with data urges or even pressures the viewer to look at data intently in the face and handle the levers of their tricky mechanisms with stress, curiosity, adrenaline, introspection, rage, and the gamut of emotions inherent in political absorption.

Central in this proposition is the depiction of extremities, specifically the head and the hands that reference what he perceives as perpetrator and fatality. These details of the precarious, inevitably violated, body are translated in terms of “objects” to be held, felt, affectively experienced. They become sculpture, installation, or relief mingling with painting, water, and everyday things. These extremities as nerve endings, so to speak, are at once vulnerable and active, exposed to so many urgencies that either diminish or supplement the agency of the finite body. The head holds a particularly Biblical valence, summoning images of John the Baptist and Holofernes and spilling over to the counter-insurgency, low-intensity conflict sensorium in which anti-communist militias in Mindanao in the eighties ensconced heads of their enemies on dishware to parade around town.

One instance in the exhibition is an outsize abacus in which the beads of the counting apparatus become heads of nameless human figures. The abacus is placed in front of a glass wall of cut-outs of data pointing to demography, mostly relating to population and mortalities. Such a demographic profile is quite exceptional in the Philippines, a country constantly bludgeoned by natural catastrophe and sustained by a swarm of people that is equivalent to the swarm of its biodiversity. Here the viewer confronts the forest and the sea of data and is tempted to interact with the abacus. When such temptation is consummated, a process of accounting of deeds takes place, with the viewer grasping the beads of heads to figure out and make sense of the statistics in relation to the humanity that is now being literally grasped. The abstraction of data gives way to the performative nature of interpreting them.

These heads re-figure on a pool of water adjacent to the abacus. This time they are buoyant stoneware, to some extent freed from the frame of the formidable abacus of hard wood. They stay afloat and collide with each other, the faces bare and staring at the expanse above them. While they may intimate some kind of an ultramarine sublime, the liquid that suspends the severed heads may remind us of water torture or “salvage” operations that end up in bodies of water.

In further iterations of the heads, the artist places them within media of weighing and serving, modalities through which sustenance is conveyed. In many ways, these are media for what is staple and necessary. For instance, there is the gantangan which is used to measure rice and other grains in the market. Then there are the found trays on which food or drinks are served. They are still life of fatal platters, referencing a veritable feeding frenzy.

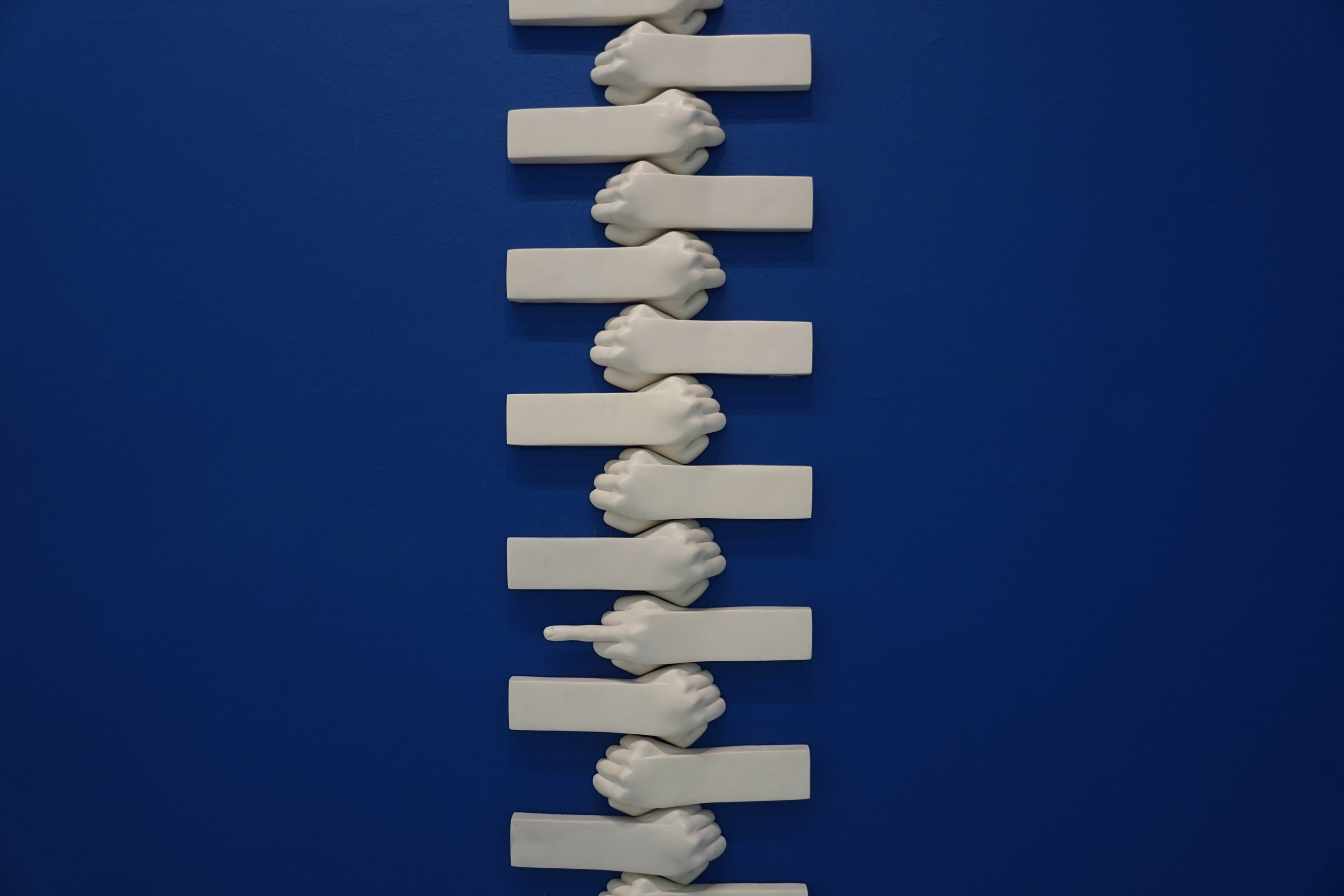

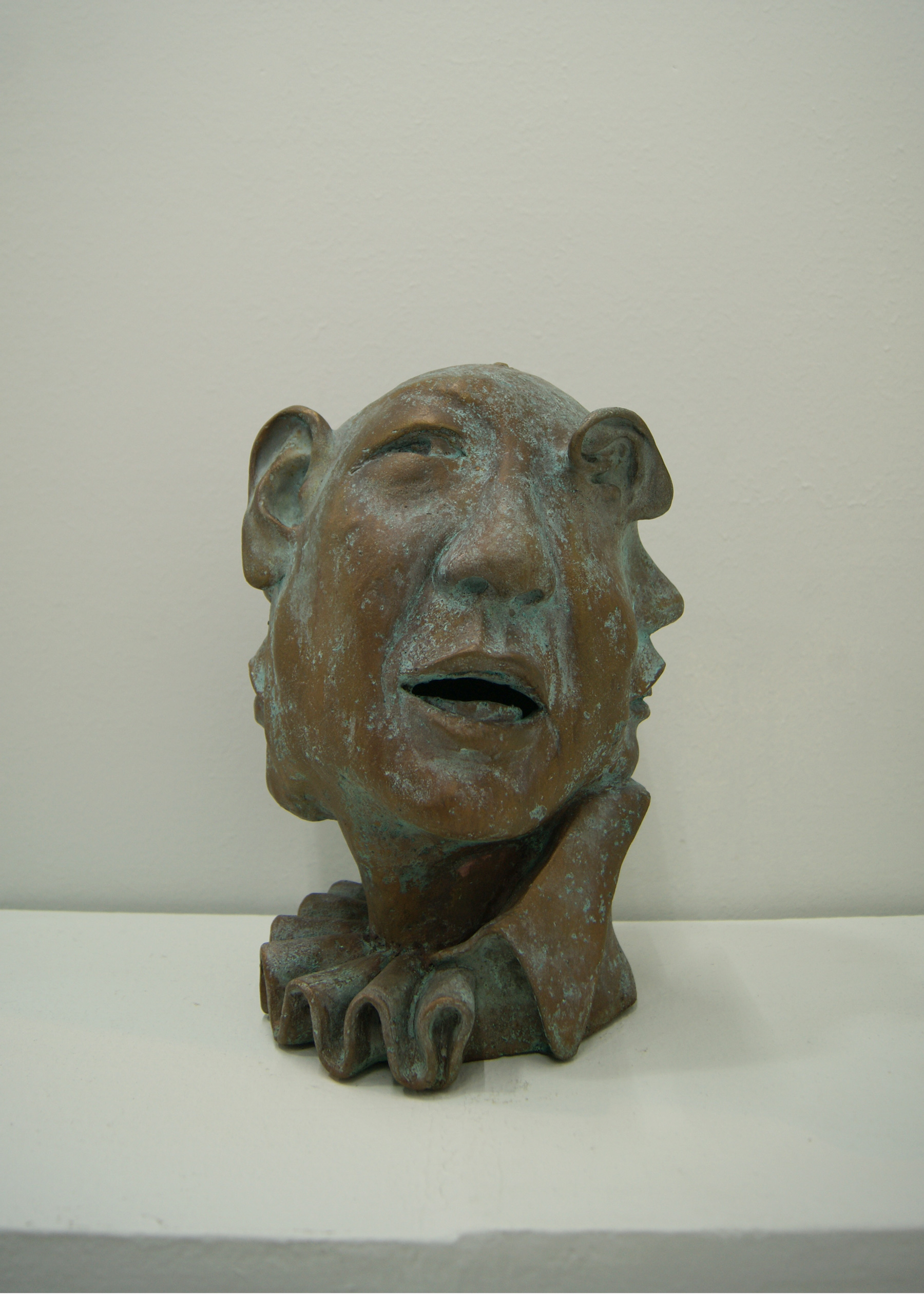

Finally, there is the morphing bust that tends to depart from the more open forms of the other pieces in the exhibition. This bust unveils recognizable figures that are made grotesque, or downright ugly. It betrays the artist’s attitude towards these figures, his judgement of their corruption as indexed by the sordid twistedness by which they are concretized. Interesting in this judgement as well is the conflation of these figures as if they were a singular changeling, a haunting continuum. The link between this bust and the striking work of a spine of hands, depicted almost ivory-like in cold-cast marble in the register of the colonial statuary, is the zipper. This spine looks like a zipper, which is the seam of the dissembling bust that mashes up the faces of what the artist regards as embodiments of political distortion. He calls it a slider, a column of forearms with clenched fists like teeth of a gigantic locked zipper. He is interested in how this contrivance is undone when one of the components misaligns or unhinges. The work anticipates a kind of undoing, of hell breaking loose, as it were.

In the recent works of the artist, the artifice finds a pivotal place. He seems to be attracted to certain contraptions that predispose habits of seeing, thinking, and feeling. In other words, they enable subjects of experience to make sense, to intuit, to institute ties. Cohering with this equipment are body parts and organs like tongue or ear or eye or hair. Resin and oil on canvas freely inhabit visual space with, for instance, Klompen or clogs and guitar parts.

Abaya titles the exhibition “Demograpi, Atbp,” roughly translated as “Demography, Etc.” It sounds commonplace, a technical description of the miscellany that comes with the register of human lives. Perhaps it is this banality, or anonymity, that is the argument of the artist. It is so pervasive that it becomes so quotidian and so collective. Cogent in his reflections is the importance of recharging the energy of the signifiers of this banality: cold data that are actually warm bodies and that, in this exhibition, become tactile and palpable sensations, almost empirical in their presence and importuning. Abaya casts these data intimately, on the one hand, and hyperbolically, on the other, the better to draw attention to their uncanny conditions as well as to their graphic exigencies. In the main, this is his critical response to the discourse and abstraction of data and the ways by which they can be made to lie or to ferret truths out of the woodwork. In the scenario of the exhibition, the viewer is prompted to make decisions on how to discern the iconographies of familiar faces and the multitude of finally kindred bodies. This is his contribution to the incendiary conversation on the current political atmosphere in which demography becomes a vector of the exchange, the word emerging from the same root of democracy.