Religious allusions abound in Renato Barja Jr.’s Kingdom of the Unwanted, a return to the artist’s sensitive portrayals of society’s bottom-dwellers. After experimenting with small paintings of unpeopled places, Barja once again trains an anthropological eye toward the gray-skinned shadows who haunt the city, their sagging bodies as ash-colored as their souls.

The exhibition consists of seven large-scale canvases, six of them accompanied by a sculpture standing about a foot-and-a-half high and another by a sketch. Save for a lone canvas depicting an empty chair, Kingdom of the Unwanted is a portrait gallery of the sick and afflicted. If a modern-day Sermon on the Mount were to take place, Barja’s vacant-eyed subjects would be among the crowds of solace-seekers. Kingdom of the Unwanted is, after all, a play on The Beatitudes and the promises made to the poor in spirit.

The oblique biblical references are rooted in Barja’s past as an altar boy, part of a Catholic upbringing shared by an overwhelming number of Filipinos. Aside from the exhibition title’s nod to the Book of Matthew, the number of paintings in the show is also significant as the number seven is endowed with religious associations: from the seven days that it took God to create the world in the Book of Genesis to the multiple instances of seven in the Book of Revelation.

An accounting of the Kingdom of the Unwanted includes Heaven’s Key, Barja’s reinterpretation of the Madonna and Child, which has been part of the iconography of Western Art since at least the third century. Mater Amabilis, the Loving Mother, is stripped of her majesty and recast as Mater Vulgaris: an anonymous everywoman, back hunched and bra strap falling off her shoulder, sleeping daughter in the cradle of one arm and a rosary clasped in the hand of the other. Poignant details revealed in the companion sculpture–a pair of mismatched shoes, a drooping belly, a small nondescript sack of belongings sitting by slippered feet–add to the painting’s narrative.

This woman is real, as are all the subjects in Barja’s growing catalog of paintings of social misfits, oddballs, and miserable ones. The Most Trusted Spy, a man who crouches gargoyle-like on a cement marker surrounded by floodwater, was someone Barja noticed from his vantage point as he too was caught out in monsoon rains while riding his bicycle. On that same rain-doused day, Barja spotted the three wall-eyed women of The Tower of Boredom: a totem of lice-pickers partially submerged in sludge.

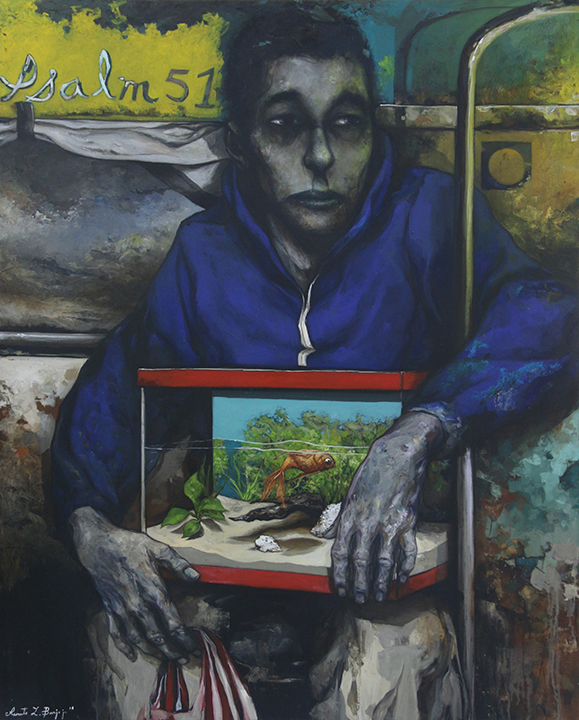

Daily commutes, whether by bicycle, by bus, or by jeepney, have always provided Barja with ample opportunity to observe the world around him; his gaze, because of some inexplicable affinity, always landing on the penurious and persecuted. Barja’s interactions with his eventual portrait subjects range from glimpses to repeated encounters. The man in Please Take the Spell You Have Me Under was a fellow passenger during a jeepney ride, the interminable kind that imposes an awkward intimacy on strangers who are seated sardine-like against their will.

The goldfish swimming in circles in its little fish tank was poetic license on Barja’s part, a metaphor for the trapped and alone.

Psalm 51, a textual element highlighted in yellow in the painting, is a scriptural reference to the verses that David wrote after committing adultery with Bathsheba. It begins: “Have mercy on me, O God, according to your unfailing love; according to your great compassion blot out my transgressions. Wash away all my iniquity and cleanse me from my sin.” Another textual detail found in the companion sculpture–the phrase Quo Vadis (Latin for “whither goest thou”) on the man’s blue sweatshirt–ratchets up the existential dread. These details, left like clues on canvas and plastic resin, flesh out the storytelling while providing a window into Barja’s psyche. While the grain of the scene is always rooted in reality, Barja composites and embellishes to get the disconsolate tenor and atmosphere that his work is known for.

The most involved pieces, The Changing of the Guards and The Kingdom of Unwanted Things, are the result of repeated sightings: both subjects are part of Barja’s routine, fixtures on his daily commute to and from his studio. The former features a man with six fingers lying in a cart that has become his home. Scattered throughout are faded and torn campaign materials–either remnants of political ambitions built on promises that will go unfulfilled, or traces of a government that could have been had the elections gone another way. At the center of it all, this man–the kind of individual that candidates would have pandered to, appealed to, and made vows to, only to be abandoned again at the end of the campaign season.

The Kingdom of the Unwanted Things features another disfigured member of society: a one-legged king seated on a tattered throne, a wealth of cigarettes at his side; his domain of junk, the last stop on Barja’s way to his studio. Barja struck up conversations with this character and found out his story: how he used to have a family; how he worked in another country; how he lost his leg, his livelihood, and his loved ones in a cruel twist of fate.

“It slapped me in the face big time,” says Barja. And this is why he paints these people: to immortalize their stories, to show them that someone, somewhen saw them and when possible, listened.

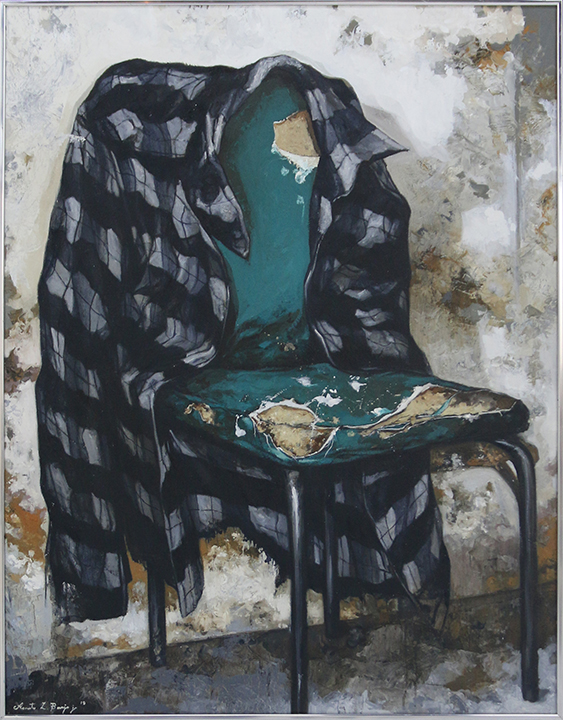

Last but not least in Kingdom of the Unwanted is Invisible Defeat, the only canvas without a central human subject. An empty chair sits in the middle; a plaid button-down draped on its back, the only sign of life. It’s a recurring motif in Barja’s exhibitions and a stand-in for his presence. (In this show, it is also present in The Changing of the Guards, hanging by the head of the sleeping subject.)

Despite the title of this self-portrait that lacks a visible self, Barja says he is neither a defeatist nor a cynic. His career, a consistent sweep of gray paint lit by small but vivid eruptions of color, may be full of melancholy to those who see the world in technicolor but to Barja, this is what is. “Nobody is asking for sympathy. This is just how I see my world,” he says. “I am only a vessel for articulating these stories about this slice of the human condition. The images are just stories, my own documentation of my landscape. I don’t know if my work will change anything but maybe, it will help someone or two polish some parts of their soul.” – ll, June 2019