There is palpable energy in Ernest Concepcion’s works. It is restless and vibrant, biding a temporal rhythm neither here nor there, not future or past, but viscerally present. Yet how do we reconcile this present or indeed, presence through objects irrevocably tied to a past - an earlier time constructed by gestures now confined within bounds of pictorial space? In variously sized mixed media paintings, Concepcion captures this irrevocable slippage through seeming spontaneity (he reveals the artistic process is replete with contemplation and reserve) and play, a concoction of industrial materials that simultaneously fuse and resist each other, an artistic relay fraught with conflict and struggle.

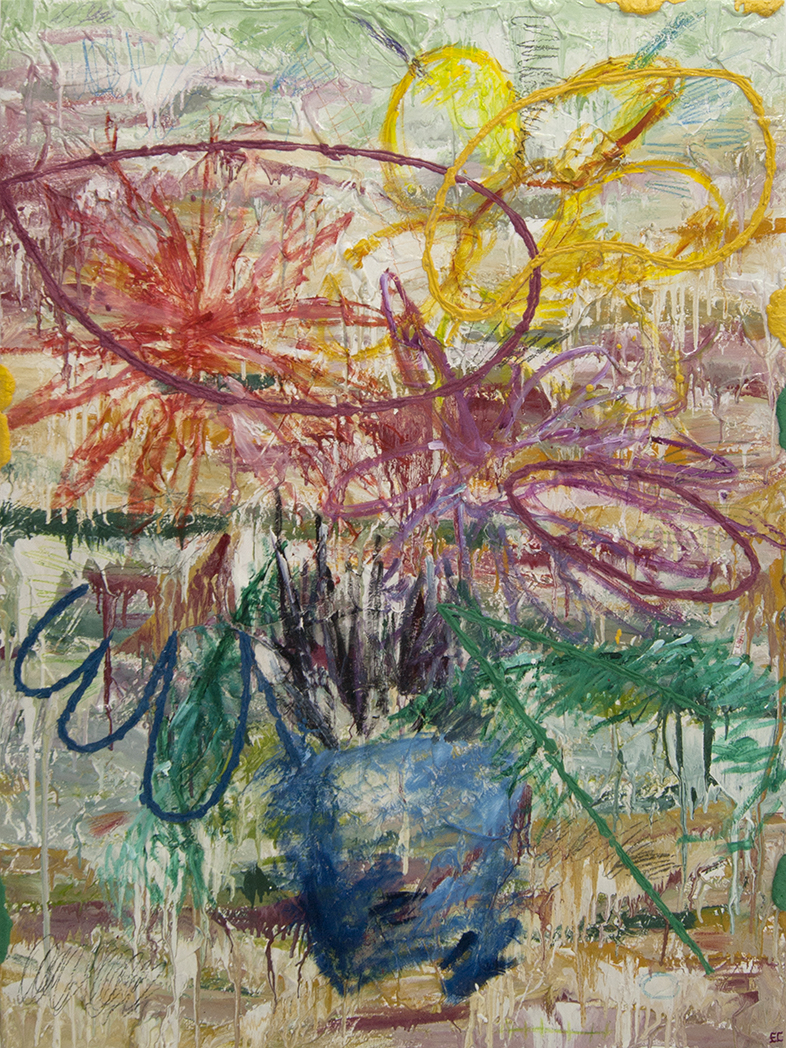

His hues are vivid and arresting, verging on the stark luminosity of unalloyed chroma. They are applied with a palette knife which explains the terrain of his canvases. Pigments are mixed with plaster and gypsum, materials that coalesce but also thwart each other. The artist builds his surface, layering over strata yet finds pleasure in sanding his ground, trimming portions, smoothing over parts, leaving out parcels; this concert of gestures resulting to hollows and mounds, webs and tangles of drips, blots, and ribbons of pigment. Lunettes, loops, and outlines of nearly indiscernible forms cement the composition into a whole. In a few, we can see traces of blooms, the silhouettes of palm trees, and clustered objects while in others, traces of fevered strokes and the insistent tactility of surfaces only remain.

Concepcion’s earlier pieces may appear a far cry from these recent ones. These were large scale paintings of defaced images of places. They were not ordinary sites but seats of power. Behind a roiling curtain of colours are fragments of a scene without figure or movement. Some ventured to call these works political commentaries but I prefer to say they were insistent transpositions of locales; echoing the artist’s own when he finally decided to relocate to Manila from years of living in New York. It may also be about the transference of a visual vocabulary, a repository of image and meaning tightly hinged to place, the experience of which is best articulated through the coordinates of time and space.

The artist initially described this suite of works as first in a series of non-representational paintings, spurred by groupings of objects, a genre familiarly known as still life. As work on the pieces progressed, it became evident they were about a persistent fascination with materials and their dynamic fusion. He particularly favours enamel, its industrial manufacture, its inherent viscosity, its glossy and vibrant range of colours. Citing several influences, a documentary on the discovery of cave paintings, viewing actual pieces by Kiefer and Barcelo in Europe; Concepcion is inspired by the unpredictable melding of material and the forms that consequently arise from the process. Concepcion’s canvases are heavy, their weight resulting from the coagulation of medium on surface. He intends for their heft to be felt and seen, and for the paintings themselves to be sturdy.

That which is not readily apparent is the artist’s shoring up of seemingly contradictory forces through the act of painting; describing his artistic process as an act or movement, pointing to the sheer physicality of painting itself. It is a series of closures and beginnings, of repose and play, of ideas and action. It is also about the passing of time, the abeyance and onslaught of thought, and the alternation of certain rhythms of crafting and viewing. He recalls earlier works labeled ‘conflict-based imagery’ perhaps because these were defaced images of representations of might. I prefer to situate this so-called conflict in the realm of figure and ground, between elements of a visual lexicon that attempts to locate the artist in the world. Concepcion notes this collision of forms mainly reside in the work but finds that in these more recent pieces, the struggle was mostly between maker and form, between himself and the work; citing the latter as his ‘sparring partner’.

How does a viewer make sense of a struggle that is past, an endeavour that unleashed great bounds of energy when all that remains are vestiges of a charged act? In the apprehension of sweeping lines and forceful strokes, abbreviations of forms and sweeps of colours, our attention is taken foremost by tactile surfaces and vibrant hues. These very attributes make the art work’s presence, a vitality petrified by static form. Perhaps we can imagine form as a vessel of time and more important, its very materiality the conduit of of a conversation whose afterglow suffuses the atmosphere we inhabit.

Ernest Concepcion imagines a receptacle for his works: the stark, white cube where colours float, bound by lines and strokes whose undulations are interrupted by craters and mounds. A vessel to contain all other vessels, a location to trace the passing of time and the salient need to locate the self. Materiality becomes a marker of time, temporality and presence are entwined, aided by the fluency of medium and its articulation through process. The artist’s choice of material is not novel, such combinations have been tried, but his compositions exude an urgency that is vibrant and vital. They speak of a need to mark a location, to be in place, so to speak. Thus, the artist’s apprehension of struggle is not confined to the limits of painting, it extends well beyond the studio of solitary practice to describe a desire that suffuses the kind of longing to belong where one is and able to be. It is longing interrupted by its twin, the restlessness that feeds the desire to roam and be elsewhere. Yet for all locations flagged in worlds imagined and inhabited, this yearning for place remains: it is what the artist fittingly captures. The works, like the feeling they imbue the viewer, speak to a miasmic restlessness, contagious and often overwhelming, befitting the frenetic cadence of our time.